Revolution! Review

Money can’t buy you happiness...but force and blackmail might.

6/9/2017

Discussing a fundamental dilemma for board game designers: what can we expect from players?

Posted on 7/8/2017 by Tim Rice

As an aspiring game designer, I have a large collection of prototypes that are in various stages of development. I’ve run a lot of different playtesting sessions for these prototypes and, of course, have heard my fair share of constructive criticism. The potential difference between how fun an idea is on paper and how fun it is in reality consistently baffles me.

Today I want to discuss a phenomenon that I haven’t read much discussion about, but has become one of my biggest design challenges. Recently, I’ve noticed that a large portion of the dilemmas I deal with for my designs can be boiled down to this one concept, and it has to do with the variance in player behavior.

My question is, in essence:

What assumptions can designers make about the players of their games, if any?

As designers, we have to make certain inevitable assumptions about how players will interact with our games. For example, a reasonable assumption might be that, before starting a game, at least one person at the table has read through the rulebook or has already played it. A designer has a responsibility to write a clear and effective rulebook, and players have a responsibility to play the game correctly.

A game designer’s job is to provide a fun experience for the players, but in order for that relationship to work, players must take on certain responsibilities as well. Problems arise when the expectations that designers put on players aren’t met, and that’s a tricky situation because player behavior is a variable that designers can’t always (and probably shouldn’t always) control. Nonetheless, it’s still an essential aspect of the game experience, so figuring out which expectations are reasonable and which aren’t is an important consideration.

In this article, I want to provide some examples of this dilemma from a designer’s perspective and offer my opinion on where certain lines should be drawn. Obviously different designers have different philosophies, and in a hobby as open-ended as board gaming there are exceptions to every rule, so I’d love to hear other opinions as well.

I once designed a prototype that featured a "dice rushing" mechanic where all players would roll several dice into a pool in the middle of the board, and then simultaneously grab dice and place them at certain areas around the table to perform actions that required certain colors/numbers to activate. The end result would be a frantic race that mixed dexterity and strategy.

This mechanic worked out pretty well, at least in my group. I decided to post it on BoardGameGeek’s board game design forum to get feedback, and one responder brought up an interesting point that I hadn’t considered.

He pointed out that it would be very easy for a dishonest player to cheat by simply picking up any die, changing it to their desired number, and placing it wherever they wanted. The thought hadn’t occurred to me because I don’t play with cheaters (either that or they’re really good at it...), but he was absolutely right, anyone that wanted to cheat could get away with it very easily.

My first thought was, it’s not my fault if people cheat at my game. They’re the ones not playing the game as it was intended, so it’s a player problem, not a design problem.....right?

The thing is, even if that’s true, it doesn’t change the fact that some percentage of playgroups will have at least one cheater, and that those experiences will be worse because the game makes it easy to cheat.

Can designers assume that players won’t cheat?

There are some mechanics that simply don’t work without this assumption, including my dice rushing idea. Think about all the games that rely on players being honest.

I’ve come around to the idea that, until we live in a perfect world where cheaters don’t exist, designers have to at least take that possibility into consideration. If a game is vulnerable to cheaters, that’s a weakness of the design, and the designer should at least think about ways that the problem could be solved. Sometimes it’ll be possible to fix the problem and still preserve the essence of the mechanic.

That being said, I don’t think designers should throw away unique and innovative mechanics just because they rely on the players’ honesty. I’d take an interesting game that I can only play with my honest friends over a fair and boring one any day. Playing fair should be a reasonable expectation to put on people, and if we put too much emphasis on designing around cheaters, we miss out on new and exciting experiences.

Designers: remember that cheaters exist.

Players: don’t cheat, and don’t play with cheaters either.

We’ve all played with that one guy who, even when playing quick-turn games like Ticket to Ride or 7 Wonders, takes five minutes per turn. The one who considers every possible option, makes a pros and cons list for each one, and solves a few multivariable calculus equations in their head in order to determine their optimal move.

Maybe that’s a slight exaggeration, but the question is, can designers assume that players will complete their turns in a reasonable timeframe? What can designers do about players that take forever? Should they do anything?

The more difficult choices a game has, the more prone it is to analysis paralysis, so one solution would be to reduce the number of choices players have to make. However, interesting decisions are what make most strategy games fun, so if you remove too many of them, the game becomes boring.

Another solution could be to set time limits on turns, but that can add a stressful element that a lot of players won’t appreciate.

At the end of the day, there’s no catch-all solution, it all depends on the experience that the designer wants to create. There are definitely things that designers can do to address this problem, but to do so, they often have to sacrifice some depth in their design. For some players, that will result in a more streamlined experience. For others, it will result in a more boring experience.

Designers: consider offering fewer options per turn, or use phases so that players can take their turns simultaneously.

Players: please try not to take forever, it’s only a game.

Consider this scenario (which is based on real-world experiences, unfortunately). Players Ann, Bill, and Charlie decide to play a game of Risk 2210 A.D., a large-scale combat game which takes several hours to complete.

After playing through most of the game, Charlie realizes that he’s fallen too far behind and no longer has any chance to achieve anything other than third place. Ann and Bill are now the only ones vying for the win. However, Charlie still has a significant number of troops, so on his last turn he decides to throw everything he has at Bill, which significantly weakens his position. Ann ends up winning not because of her own actions in the game, but because Charlie stopped trying to win, and instead set his sights on destroying Bill.

This is what’s known as kingmaking, and it’s just one example of how a game can fail if players’ motivations aren’t in sync with each other. It seems obvious that a player’s motivation should always be to win, but clearly that isn’t always the case.

Can designers assume that players will always try to win?

Many multiplayer competitive games are "balanced" only by the assumption that the players will constantly go after the person that they perceive to be in the lead, so that they can improve their own ranking. In theory, if everyone constantly bashes the leader, the lead will always be near the grasp of all players.

In cases like these, problems arise when players, for whatever reason, don’t try to win. Intentionally or not, this decision affects the experience of all the other players who are trying to win, and it is often counterproductive to what the designer intended.

However, people enjoy games for different reasons. If a player would rather try a silly strategy or mess with everyone else as much as possible than win, shouldn’t they be able to make that choice? It is a tough situation when players have different criteria for a successful game, especially in games that are highly interactive.

Designers: when designing, think about how a player that doesn’t play to win can affect the experience for everyone else.

Players: just because the rules say you can do something, it doesn’t mean it’s in the spirit of the game. Play games the way you want to, but keep sportsmanship in mind as well.

So far we’ve covered expectations about players interacting with the game itself, but when you start trying to predict how players will interact with each other, it gets even more complicated. Sometimes, players have differing expectations about how a game should be played.

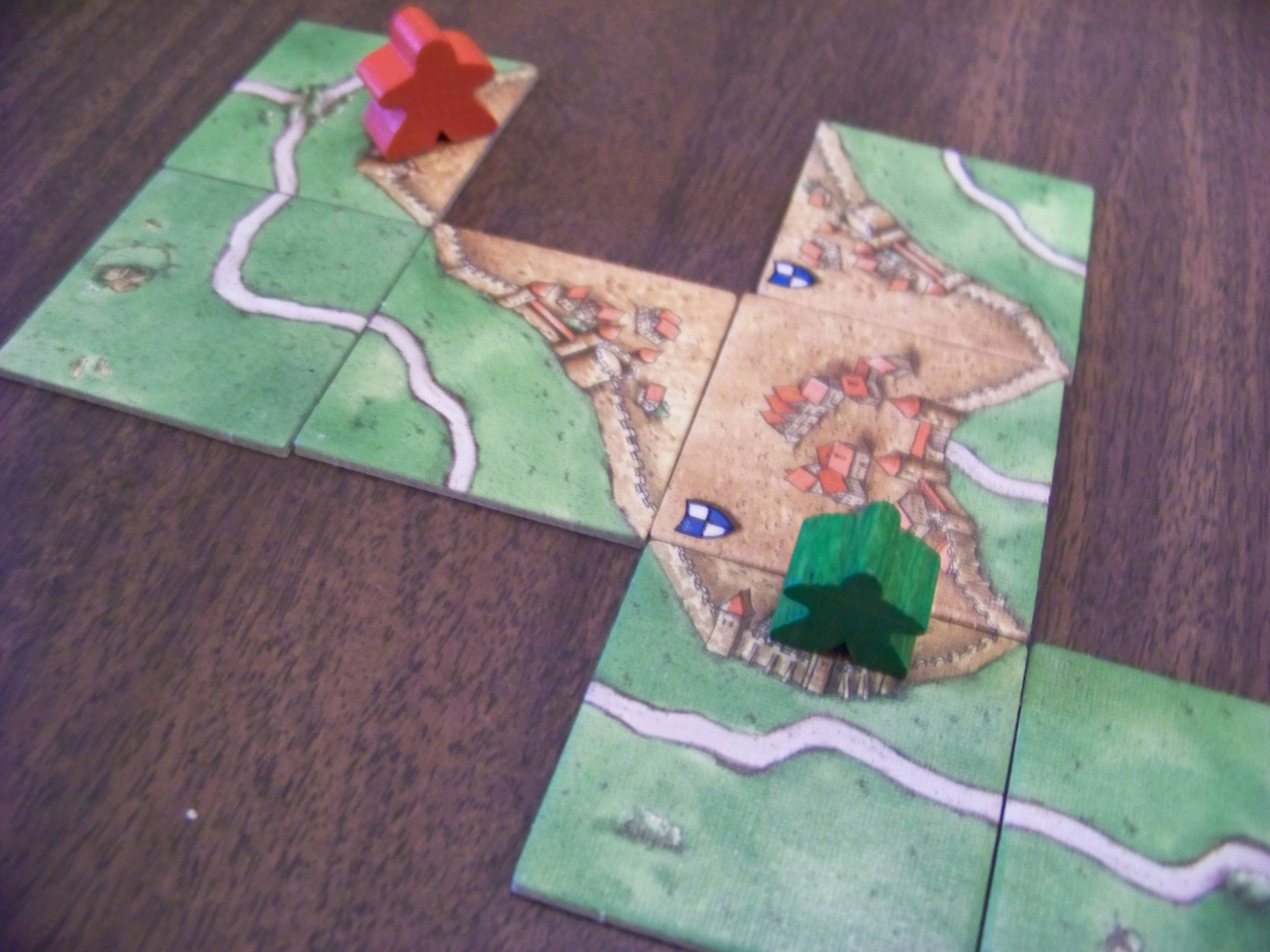

I have a personal example; consider Carcassonne. Whenever I play the game, there are always people that get very upset if I impede their progress in some way or try to get my meeples into their cities. A lot of what I enjoy about the game is the player interaction that comes from competing for high-scoring cities and blocking each other whenever there’s a good opportunity. Without that aspect, it’s not far from a solitaire puzzle.

But not everyone enjoys the game for the same reasons that I do. Some people prefer to build up their own features, help the board grow elegantly, and avoid other people’s features whenever possible. I had to stop playing it the way I enjoy because it was causing too many hard feelings.

These two experiences are at odds with each other because the player’s expectations of how the game should be played are at odds with each other. I often wonder whether Wrede intended to design the cutthroat game that I enjoy, the peaceful game that others enjoy, or both. Either way, when people from different points of view play each other, it causes problems.

Can designers assume that players’ feelings won’t get hurt?

This one is pretty easy, the answer is no. You might think that it’s silly and pointless to get upset over someone else’s actions while playing a game; it’s only a dumb game after all, there are no real-life consequences. You’d be right of course, but can you honestly tell me that you’ve never gotten upset at someone for doing something to you in a game?

I’d be lying if I said that I never have. When my fiancée, who I trusted and listened to throughout an entire game of The Resistance, turned out to be a grubby spy… I was not happy. When a friend made a ceasefire deal with me on the European border in Risk only to betray me the very next turn… I was not happy. Human nature is not a trivial force to overcome, and being betrayed and lied to is hurtful, even if it is just a game.

There are groups out there that want nothing more than to backstab and destroy each other all day long, and they’re perfectly happy doing so. I have a hard time believing that they’re in the majority, however. Know that if your design includes opportunities to create tension, some players are going to take them, and some players won’t take them so well.

Designers: accept that some players will get upset in games and keep that in mind when designing interactive mechanics.

Players: it’s cliché, but remember that winning doesn’t matter, what matters is having fun and spending time together.

Predicting what players will do is no easy task, it’s one of the main things that makes game design so difficult. It’s why a lot of ideas sound great in theory, but fall apart in practice. When the variable that is the player’s brain turns out to be a value that the designer doesn’t expect, the equation can become unsolvable.

When designing, it isn’t safe to assume much of anything about players if you can help it. Instead, make choices that benefit your target audience. If you’re targeting families/non-gamers, maybe don’t include that rondel mechanic you were considering. If you’re targeting heavy eurogamers, maybe add nine more of them.

There’s never going to be a game that appeals to everyone (just look at some of the comments and ratings for Pandemic Legacy, the highest-rated game on BoardGameGeek at the moment). That’s why it’s important for designers to choose which type of player they want to design for, and keep them in mind throughout the design process.

Often, the very same thing that one player hates about a game will be another player’s favorite part, and that’s OK. One of the best things about board gaming is the boundless variety of experiences; not only in the games themselves, but also in the people you play them with.

Thanks for reading!